Chapter 2

Atoms, Molecules, and Ions

Shaun Williams, PhD

The Early History of Chemistry

Early History of Chemistry

- Greeks were the first to attempt to explain why chemical changes occur.

- Alchemy dominated for 2000 years.

- Several elements discovered.

- Mineral acids prepared.

- Robert Boyle was the first "chemist".

- Performed quantitative experiments.

- Developed first experimental definition of an element.

Fundamental Chemical Laws

Three Important Laws

- Law of conservation of mass (Lavoisier):

- Mass is neither created nor destroyed in a chemical reaction.

- Law of definite proportion (Proust):

- A given compound always contains exactly the same proportion of elements by mass.

- Law of multiple proportions (Dalton):

- When two elements form a series of compounds, the ratios of the masses of the second element that combine with 1 gram of the first element can always be reduced to small whole numbers.

Dalton's Atomic Theory

Dalton's Atomic Theory (1808)

- Each element is made up of tiny particles called atoms.

- The atoms of a given element are identical; the atoms of different elements are different in some fundamental way or ways.

- Chemical compounds are formed when atoms of different elements combine with each other. A given compound always has the same relative numbers and types of atoms.

- Chemical reactions involve reorganization of the atoms - changes in the way they are bound together.

- The atoms themselves are not changed in a chemical reaction.

Gay-Lussac and Avogadro (1809-1811)

- Gay—Lussac

- Measured (under same conditions of T and P) the volumes of gases that reacted with each other.

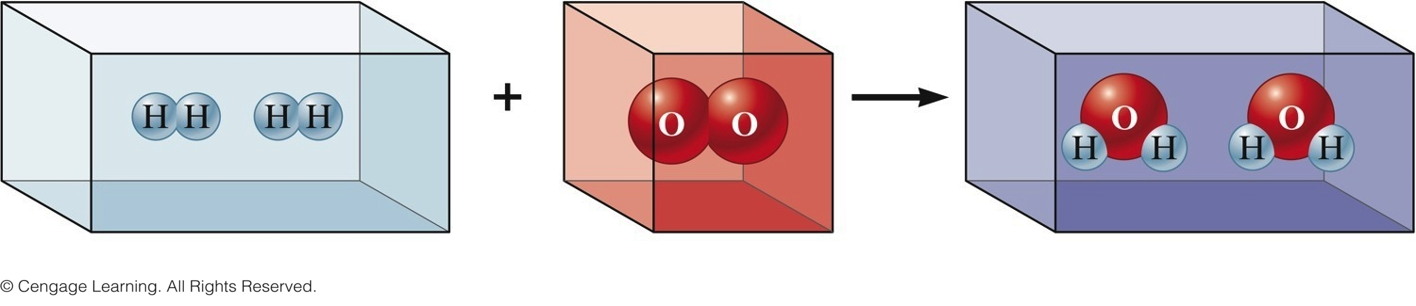

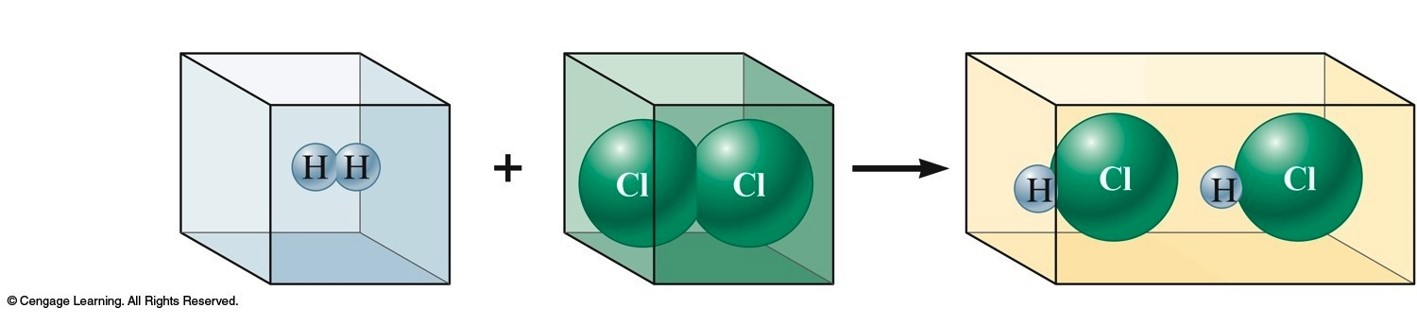

- Avogadro’s Hypothesis

- At the same T and P, equal volumes of different gases contain the same number of particles.

- Volume of a gas is determined by the number, not the size, of molecules.

- At the same T and P, equal volumes of different gases contain the same number of particles.

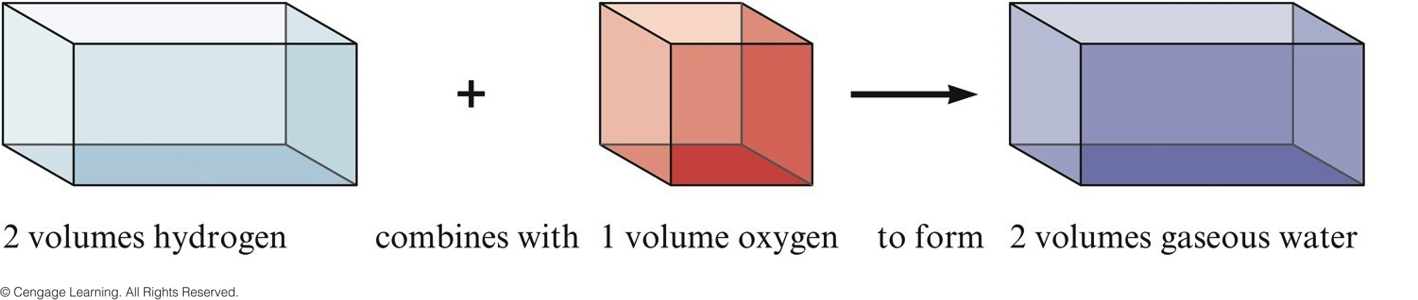

representing Gay-Lussac's Results 1

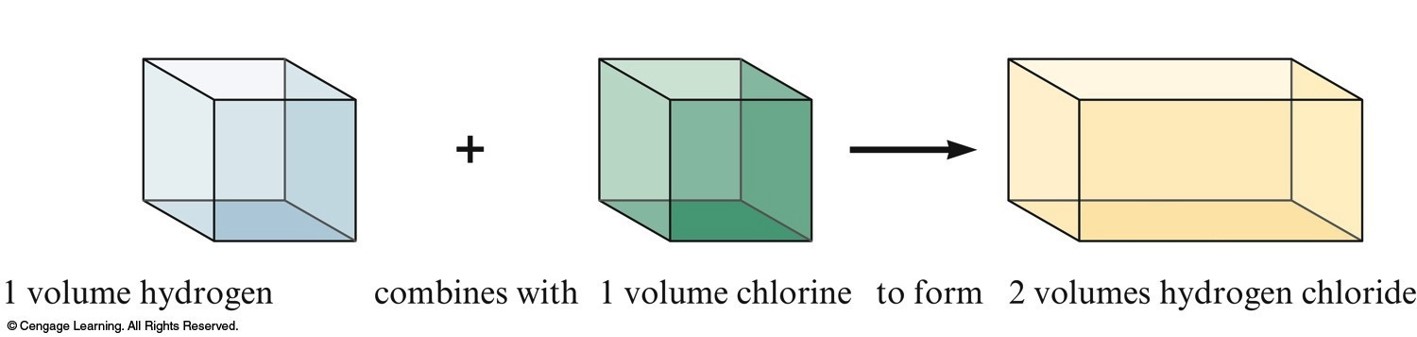

Representing Gay-Lussac's Results 2

Early Experiments to Characterize the Atom

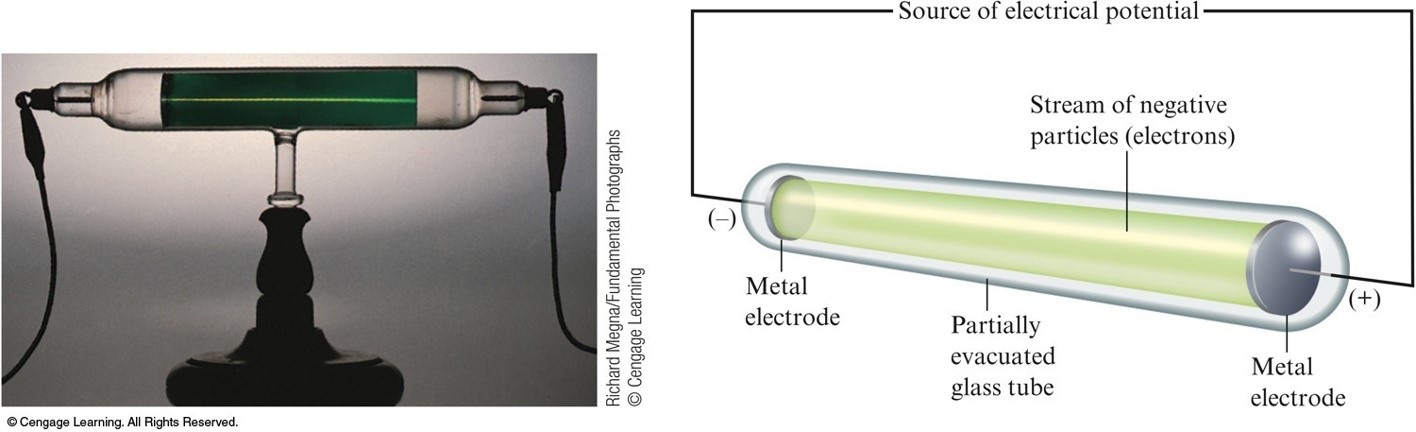

J. J. Thomson (1898-1903)

- Postulated the existence of negatively charged particles, that we now call electrons, using cathode-ray tubes.

- Determined the charge-to-mass ratio of an electron.

- The atom must also contain positive particles that balance exactly the negative charge carried by electrons.

Carthode-Ray Tube

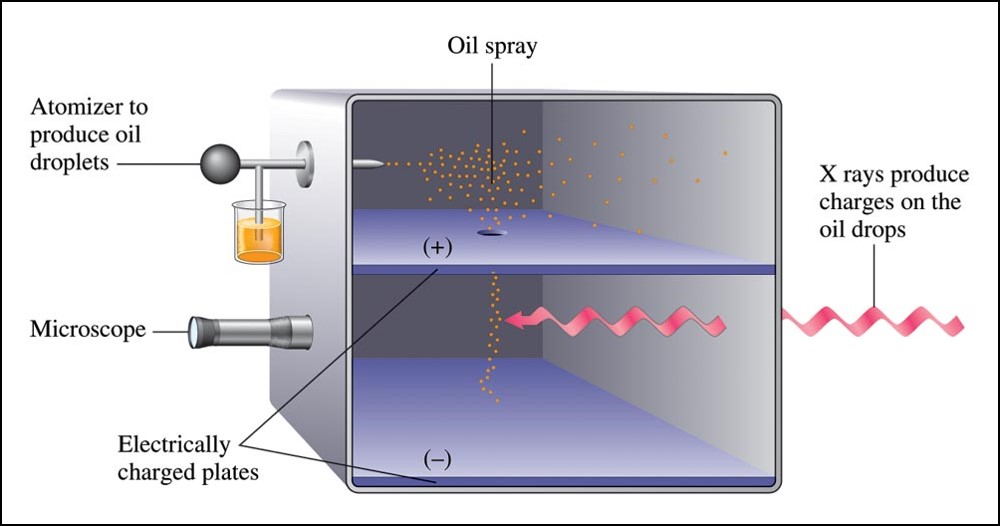

Robert Millikan (1909)

- Performed experiments involving charged oil drops.

- Determined the magnitude of the charge on a single electron.

- Calculated the mass of the electron

- \((9.11 \times 10^{-31}\,\chem{kg})\).

Millikan Oil Drop Experiment

Millikan Oil Drop Experiment - Animation

Henri Becquerel (1896)

- Discovered radioactivity by observing the spontaneous emission of radiation by uranium.

- Three types of radioactive emission exist:

- Gamma rays (\(\gamma\)) – high energy light

- Beta particles (\(\beta\)) – a high speed electron

- Alpha particles (\(\alpha\)) – a particle with a 2+ charge

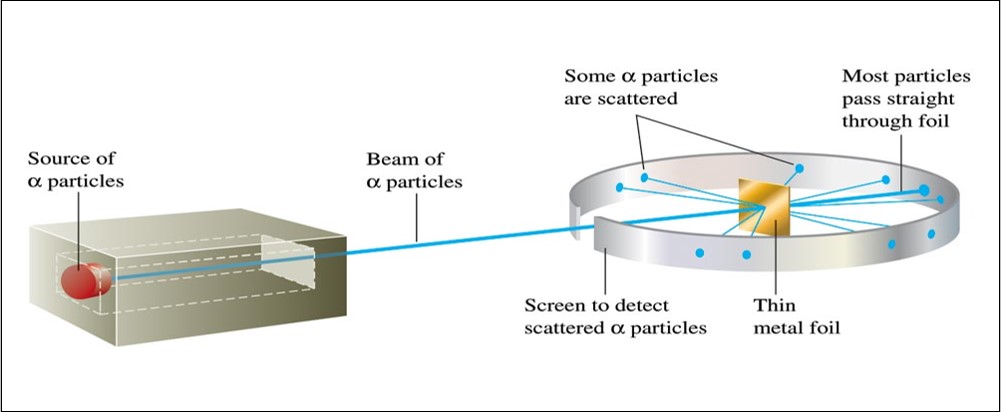

Ernest Rutherford (1911)

- Explained the nuclear atom.

- The atom has a dense center of positive charge called the nucleus.

- Electrons travel around the nucleus at a large distance relative to the nucleus.

Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment

Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment - Animation

Rutherford's Gold Foil Experiment Results

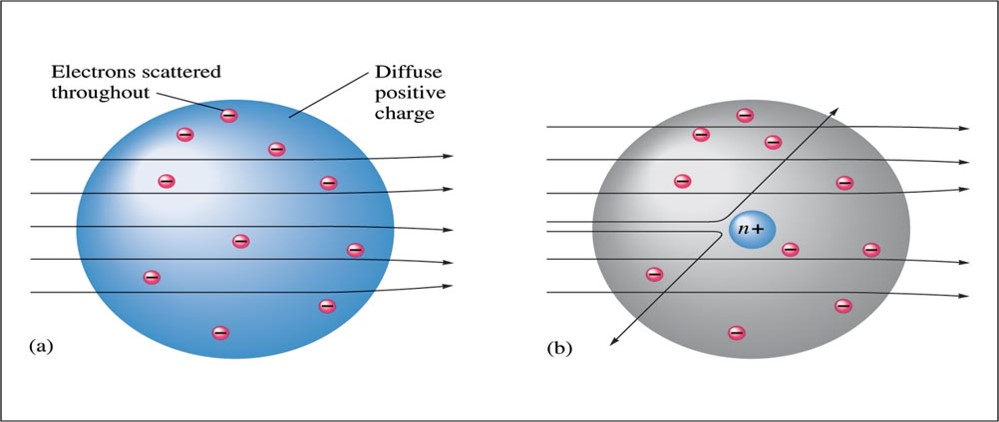

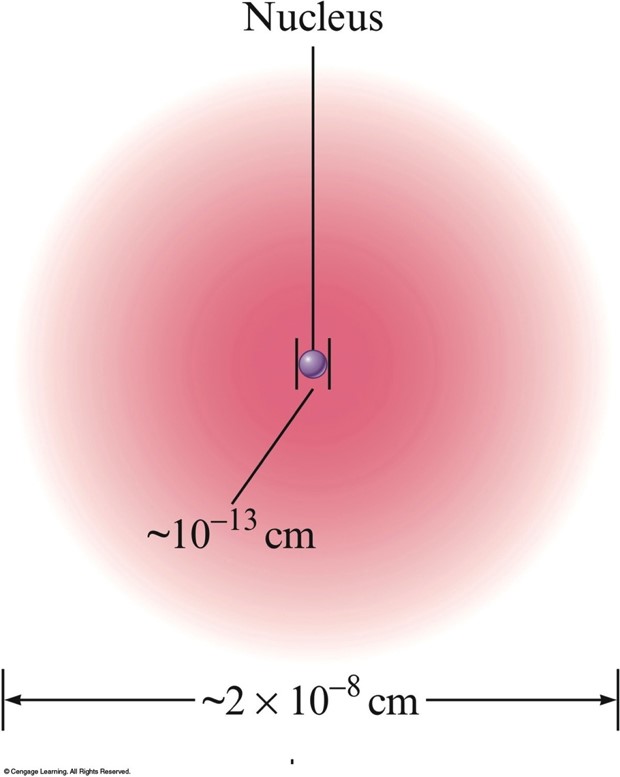

The Modern View of Atomic Structure: An Introduction

The Modern Atom

- The atom contains:

- Electrons – found outside the nucleus; negatively charged.

- Protons – found in the nucleus; positive charge equal in magnitude to the electron’s negative charge.

- Neutrons – found in the nucleus; no charge; virtually same mass as a proton.

- The nucleus is:

- Small compared with the overall size of the atom.

- Extremely dense; accounts for almost all of the atom’s mass.

Nuclear Atom Viewed in Cross Section

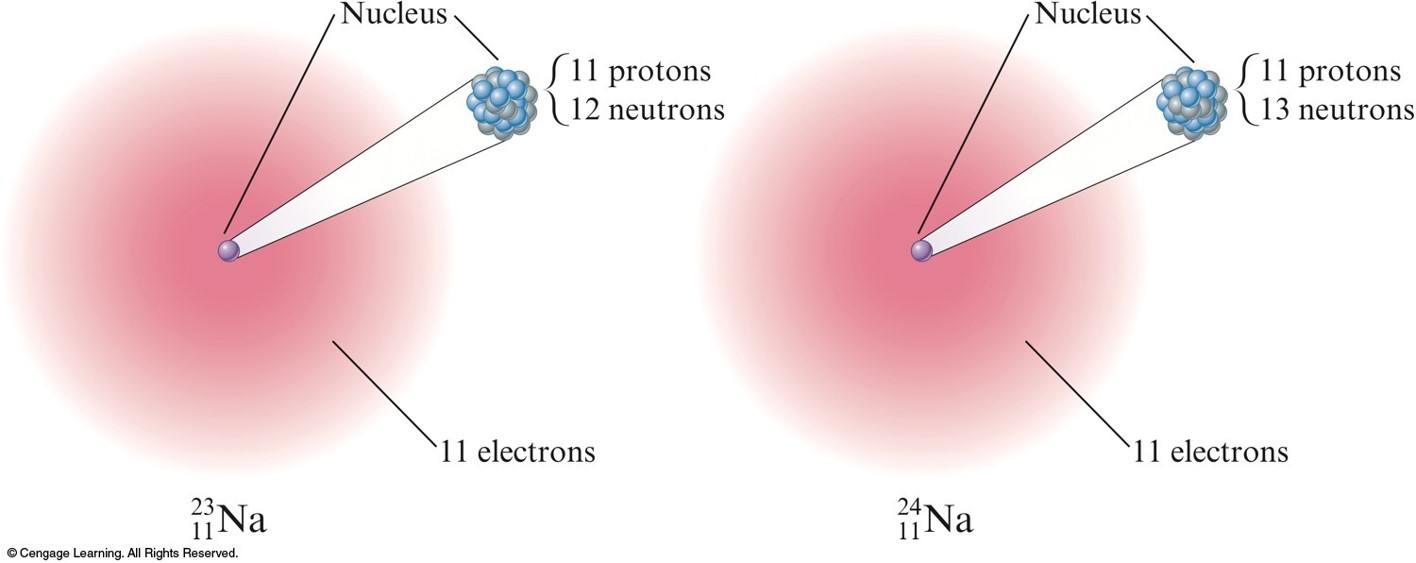

Isotopes

- Atoms with the same number of protons but different numbers of neutrons.

- Show almost identical chemical properties; chemistry of atom is due to its electrons.

- In nature most elements contain mixtures of isotopes.

Two isotopes of sodium

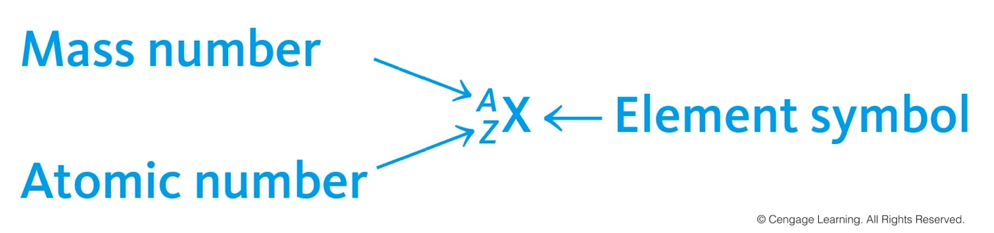

Isotope Symbols

- Isotopes are identified by:

- Atomic Number (Z) – number of protons

- Mass Number (A) – number of protons plus number of neutrons

Molecules and Ions

Chemical Bonds

- Covalent Bonds

- Bonds form between atoms by sharing electrons.

- Resulting collection of atoms is called a molecule.

- Ionic Bonds

- Bonds form due to force of attraction between oppositely charged ions.

- Ion – atom or group of atoms that has a net positive or negative charge.

- Cation – positive ion; lost electron(s).

- Anion – negative ion; gained electron(s).

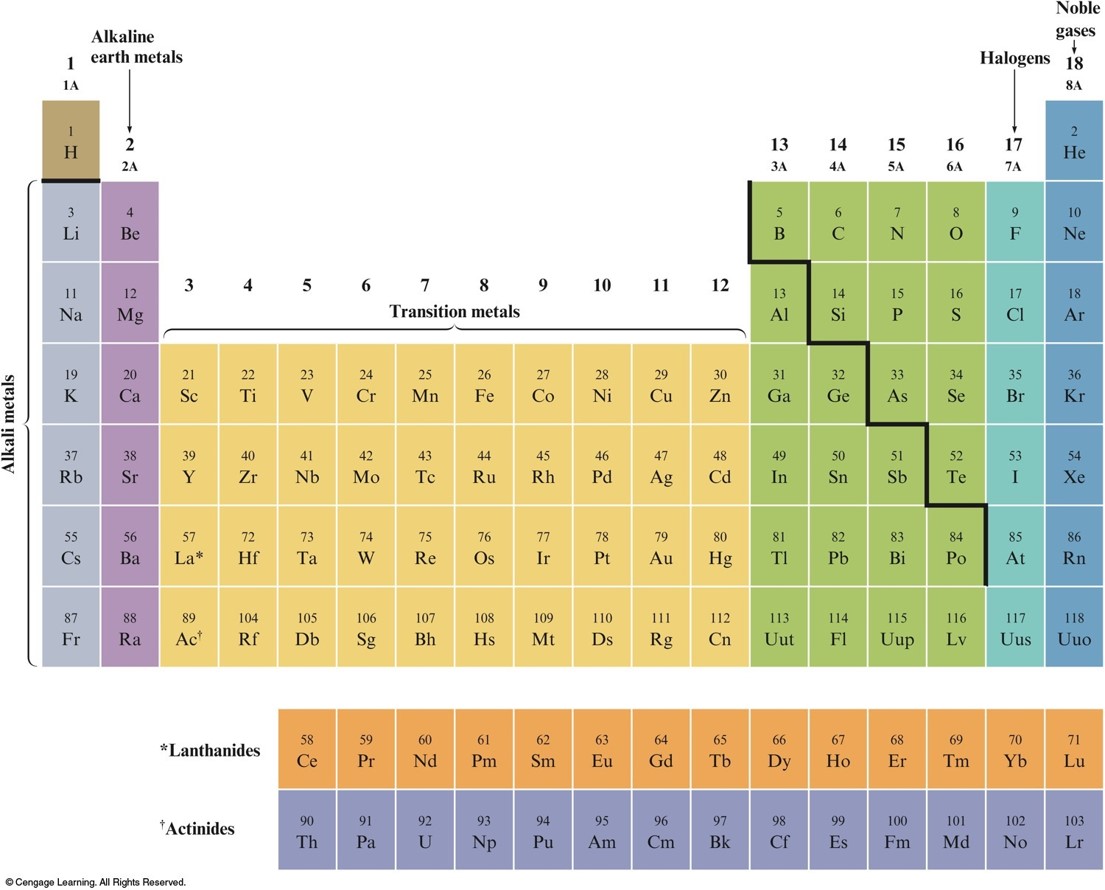

An Introduction to the Periodic Table

The Periodic Table

- Metals vs. Nonmetals

- Groups or Families – elements in the same vertical columns; have similar chemical properties

- Periods – horizontal rows of elements

Groups or Families

- Table of common charges formed when creating ionic compounds.

| Group or Family | Charge |

|---|---|

| Alkali Metals (1) | 1+ |

| Alkaline Earth Metals (2) | 2+ |

| Halogens (17) | 1- |

| Noble Gases (18) | 0 |

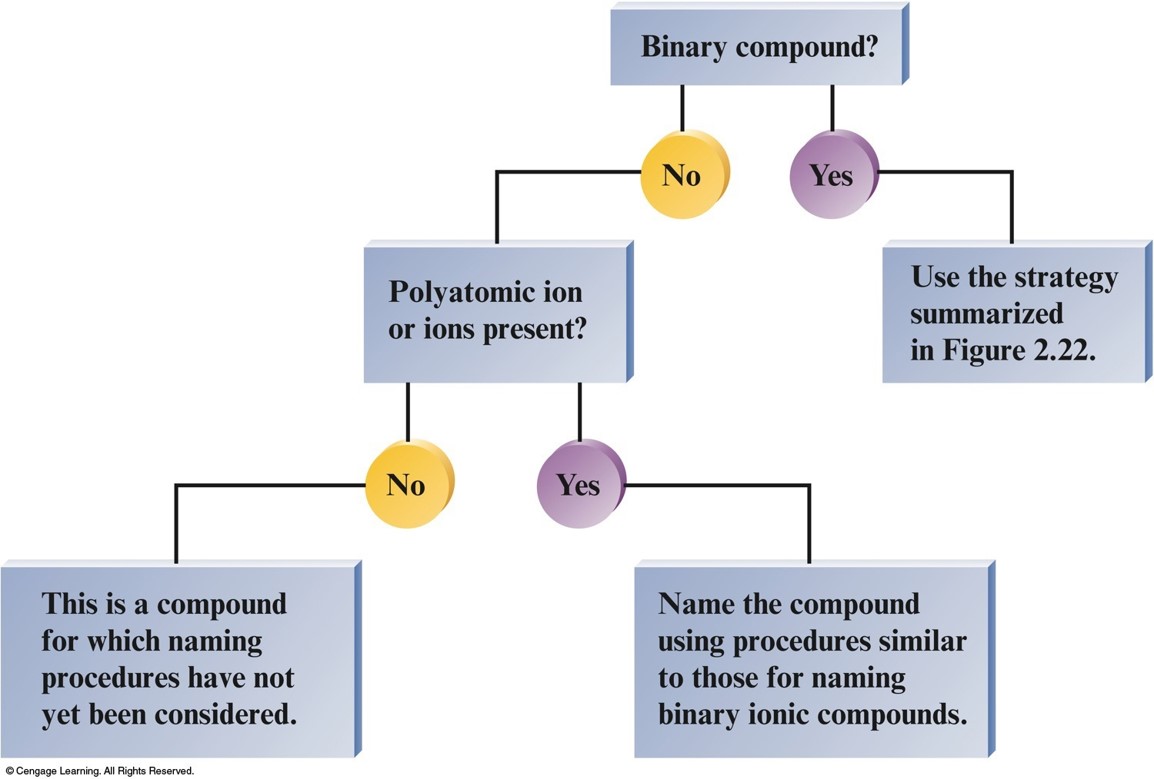

Naming Simple Compounds

Naming Compounds

- Binary Compounds

- Composed of two elements

- Ionic and covalent compounds included

- Binary Ionic Compounds

- Metal—nonmetal

- Binary Covalent Compounds

- Nonmetal—nonmetal

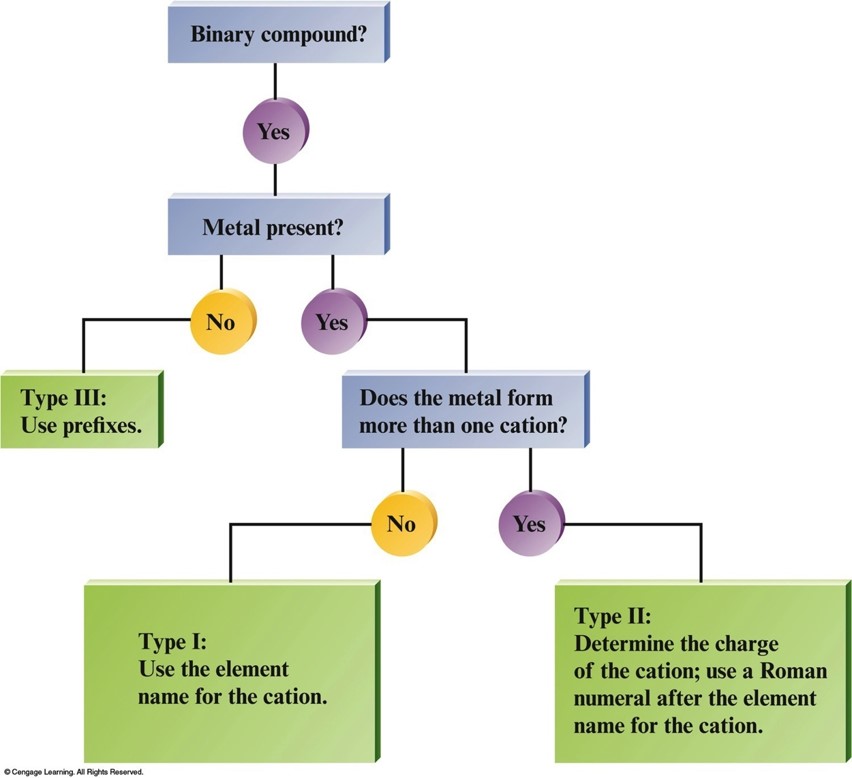

Binary Ionic Compounds (Type I)

- The cation is always named first and the anion second.

- A monatomic cation takes its name from the name of the parent element.

- A monatomic anion is named by taking the root of the element name and adding –ide.

- Examples

- \(\chem{KCl}\) - Potassium chloride

- \(\chem{MgBr_2}\) - Magnesium bromide

- \(\chem{CaO}\) - Calcium oxide

Binary Ionic Compounds (Type II)

- Metals in these compounds form more than one type of positive ion.

- Charge on the metal ion must be specified.

- Roman numeral indicates the charge of the metal cation.

- Transition metal cations usually require a Roman numeral.

- Elements that form only one cation do not need to be identified by a roman numeral.

- Examples

- \(\chem{CuBr}\) - Copper(I) bromide

- \(\chem{FeS}\) - Iron(II) sulfide

- \(\chem{PbO_2}\) - Lead(IV) oxide

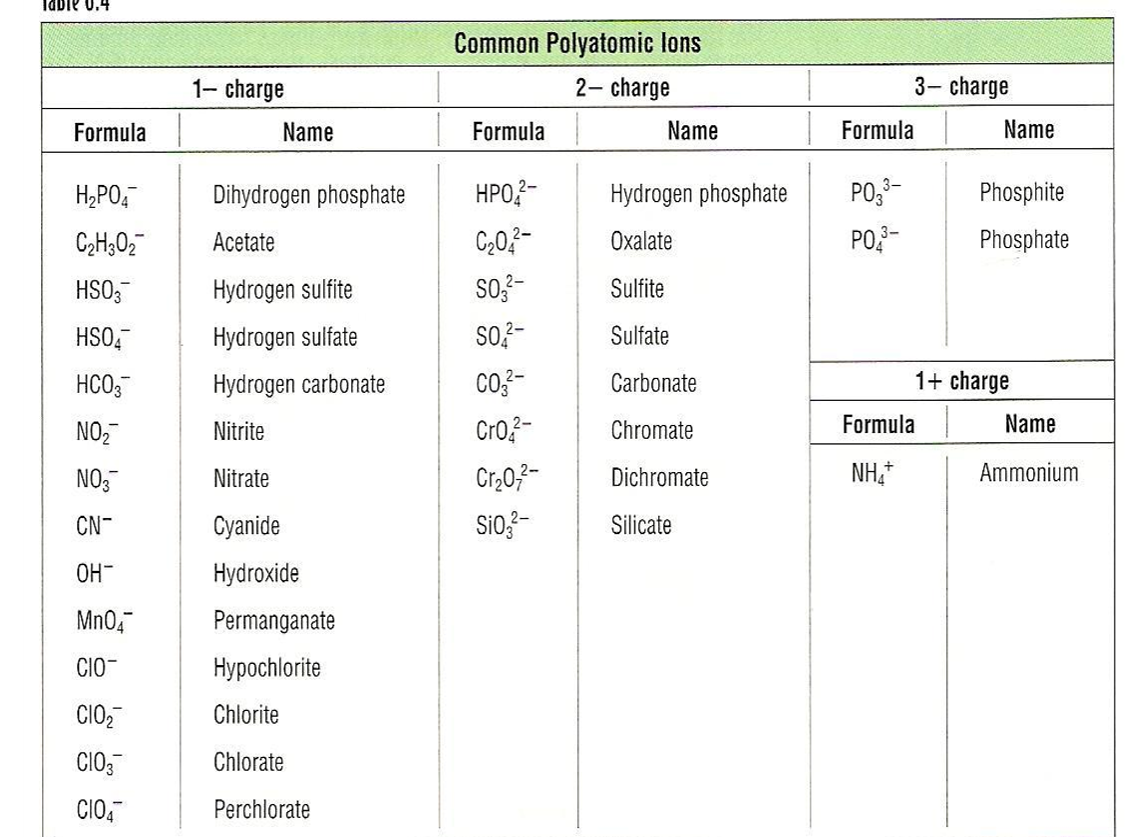

Polyatomic Ions

- Must be memorized (see Table 2.5 on pg. 65 in text).

- Examples of compounds containing polyatomic ions:

- \(\chem{NaOH}\) - Sodium hydroxide

- \(\chem{Mg(NO_3)_2}\) - Magnesium nitrate

- \(\chem{(NH_4)_2SO_4}\) - Ammonium sulfate

Common Polyatomic Ions

Binary Covalent Compounds (Type III)

- Formed between two nonmetals.

- The first element in the formula is named first, using the full element name.

- The second element is named as if it were an anion.

- Prefixes are used to denote the numbers of atoms present.

- The prefix mono- is never used for naming the first element.

| Prefix | Number | Prefix | Number | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| mono- | 1 | di- | 2 | |

| tri- | 3 | tetra- | 4 | |

| penta- | 5 | hexa- | 6 | |

| hepta- | 7 | octa- | 8 | |

| nona- | 9 | deca- | 10 |

Binary Covalent Compounds (Type III) - Examples

- \(\chem{CO_2}\) - Carbon dioxide

- \(\chem{SF_6}\) - Sulfur hexafluoride

- \(\chem{N_2O_4}\) - Dinitrogen tetroxide

Flowchart for Naming Binary Compounds

Overall Strategy for Naming Chemical Compounds

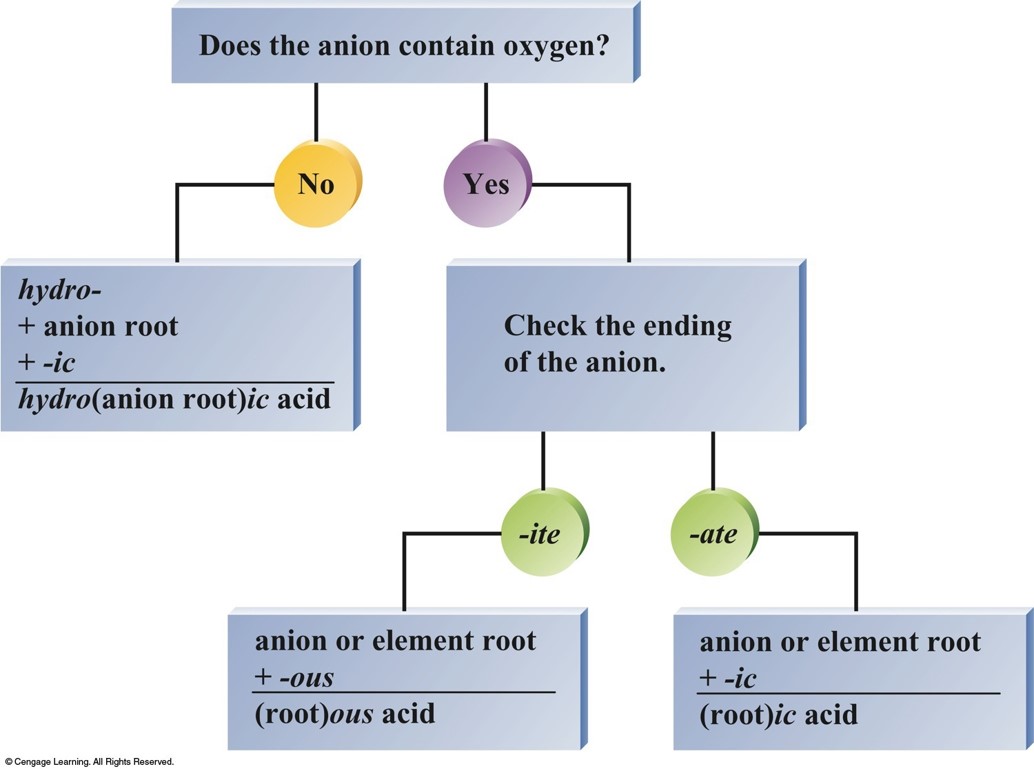

Acids

- Acids can be recognized by the hydrogen that appears first in the formula -\(\chem{HCl}\).

- Molecule with one or more \(\chem{H^+}\) ions attached to an anion.

- If the anion does not contain oxygen, the acid is named with the prefix hydro– and the suffix –ic.

- Examples

- \(\chem{HCl}\) - Hydrochloric acid

- \(\chem{HCN}\) - Hydrocyanic acid

- \(\chem{H_2S}\) - Hydrosulfuric acid

Acids (cont.)

- If the anion does contain oxygen:

- The suffix –ic is added to the root name if the anion name ends in –ate.

- Examples:

- \(\chem{HNO_3}\) - Nitric acid

- \(\chem{H_2SO_4}\) - Sulfuric acid

- \(\chem{HC_2H_3O_2}\) - Acetic acid

- If the anion does contain oxygen:

- The suffix –ous is added to the root name if the anion name ends in –ite.

- Examples:

- \(\chem{HNO_2}\) - Nitrous acid

- \(\chem{H_2SO_3}\) - Sulfurous acid

- \(\chem{HClO_2}\) - Chlorous acid

Flowchart for Naming Acids

/